From the St Louis Post Dispatch

Sunday, April 19, 1970

Gerald J. Meyer of the P-D Staff

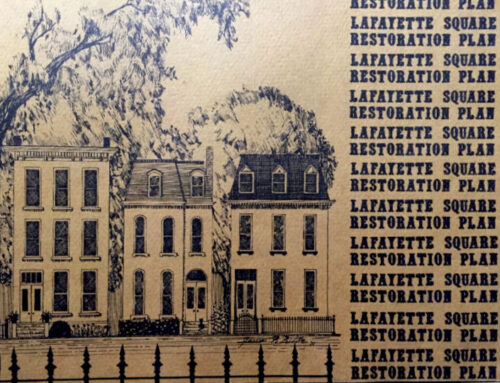

Editor note: The following article is verbatim, with only the specific homeowner profiles summarized. The newspaper itself was in such tough shape that this article was retyped and the photos added back. As a document, it’s key to understanding the mindset of the first Lafayette Square restorationists in the 1970s, and the original rationale for the Lafayette Square Restoration Committee (LSRC), now in its 50th year.

Move to Restore Lafayette Square

Lafayette Park this spring is exactly what it has been through more than a hundred springs – an oasis of serenity in the heart of the city. It is a place that the automobile age seemingly has never really touched, somehow. It appears suspended in 1890, haunted by carriages and crinoline skirts. History hangs in its air.

And the Lafayette Square neighborhood around the park remains today much as it has been for decades – admired, sentimentalized, neglected. A few of the grand old houses, once the pride of some of St. Louis’s grandest families are leaning even more dangerously than they leaned last year. Some stand empty, boarded up or gutted by thieves. Many are rooming houses, and most are in an advanced state of disrepair.

Visitors drive into the area, as they have for decades, and cluck their tongues in amazement and regret. Then they drive away, as they have for decades, to more fashionable places. And Lafayette Square, like a Victorian spinster whose money has run out, is left to its slow decline.

But this spring there are signs that something significantly new is happening in the area. Some of the people who come every weekend to look at the Square, to find food for their daydreams about a lost past, are finding it impossible to go away. They are staying, some of them, and buying and restoring houses. They are betting heavily – betting more than everything they own, in some cases – that a rebirth of Lafayette Square is at hand.

There are not many of these people yet – perhaps 20, owning about 10 houses. But they have two enormous assets. They are absolutely in love with their homes, with the big stately rooms and the high ceilings and the massive hand-carved woodwork. And they are confident that the neighborhood is going to be saved. Their confidence is of the fierce kind that sometimes makes prophesy self-fulfilling.

The newcomers are creating a hopeful mood for the neighborhood, and that mood may prove to be more important than physical preservation of buildings. A few houses in the area have never seriously deteriorated, and some limited rehabilitation began as early as three years ago. But the number of well-preserved buildings has been small for a long time, and until this year it has continued to grow smaller.

Now, with much of the neighborhood seemingly on the threshold of final decay, the number of well-kept houses is slowly but surprisingly beginning to grow. Growing with it is a contagious belief that the Square is moving towards a future as brilliant as its beginnings, when it was a residential showplace of the Midwest.

Editor – Following this was a profile of 24-year old Steve Noskowitz and Ed Pudney, two young men from New York. They paid $6000.00 for 9 Benton Place, a house with 11 rooms and 6000 square feet of living space. In 1969, they invested over $20,000 in extensive alterations to the home; new heating, plumbing, foundation work, flooring and a new kitchen. The two put in a lot of sweat equity, despite neither having a background in construction. They re-landscaped, rerouted the drainage of the house, and repainted the exterior. Both men were propelled by the thought that they would end up with an elegant home on a private street, and would have been unable to match that in the suburbs.

Editor – Then came a profile of Tim Conley, 22 years old, and a teacher in East St.Louis. He was living with his parents and fell in love when he first saw Lafayette Square. He bought 2043 Park Avenue for $12,500 and had been working on the former boarding house since September of 1969. He had hauled tons of junk from the house, repaired wiring, plumbing, plaster, woodwork and floors. He called it the “most rewarding thing I’ve ever done in my life”, and that even though he put all his savings and all he was then earning into the house, he never once regretted it.”

Editor – Finally, a profile of Walter and Pat Jenkins, also in their early 20s, who left Clayton to buy the house at 15 Benton Place. The 10 room three story place cost them $5,250, which they raised with help from their relatives. Also once a boarding house, it was structurally sound and they were able to get away with relatively inexpensive updates, and repairs to woodwork and walls. One of their workers was a friend living with them, Jim Meyer, who wanted to buy a home in the Square, but couldn’t secure a mortgage loan, due to his 1-A draft status.

Pat Jenkins said, “Everybody loves it here. There’s a great community spirit – we get together to help with each other’s projects and compare notes. Our whole outlook on things has changed since we got here.”

Many Lafayette newcomers were alarmed earlier this year when the Barlow mansion, a historic and well-preserved structure on Mississippi Avenue and Kennett Place, was vacated, stripped by thieves, set fire to by vandals, and finally torn down. The destruction of the building precipitated the formation of a new residential group, the Lafayette Square Restoration Committee, as a device for fighting to save other buildings and preserve the character of the neighborhood.

“When the Barlow house was stripped and then demolished, we thought perhaps if we’d been organized we might hav been able to save it, Noskowitz explains, “And we started to think that we needed some way to save what’s left of these wonderful old homes.”

The chief goals of the committee are to encourage families to buy and restore homes in the area and to have the neighborhood declared a historic landmark area in which homes may not be demolished without special permission from the City Plan Commission.

One of the group’s central ideas is that Lafayette Square must be restored by individual homeowners, not by urban renewal corporations or government agencies attempting to find housing for the poor. Members are markedly unenthusiastic about government proposals for construction of a turnkey housing project on a nearby street.

“These houses are too beautiful and too important to be good housing for poor people,” Noskowitz said. “They are great family homes, period. The only thing that will save this neighborhood is for black and white people with some money and a lot of determination to come in. Helping the poor is important, but it just doesn’t have much to do with the needs of Lafayette Square.”

Restoration committee members say they are determined that any restorable houses vacated in the future will not be left to damage as the Barlow Mansion was. “We’ll go and board up the doors and windows ourselves if that’s what we have to do to save the houses for people interested in buying them,” Jenkins said.

To the committee members, prospective buyers are the world’s most beautiful people. They know that their own success depends ultimately upon the willingness of others to follow their example. They express absolute confidence that plenty of followers will come, and soon.

“We’re always watching the situation, of course, and we have the feeling that this spring things are really going to mushroom,” Noskowitz added. “People are hearing about what we’re doing and they’re beginning to get interested. I think that by the end of summer this place is really going to be moving ahead.”

Despite the enthusiasm with which serious house-shoppers are welcomed to the Square, the merely curious are said to have become something of a problem in recent months, especially on weekends.

“We’ve spent such a lot of time showing people through our house, hoping to get them in with us,” Noskowitz said. “I’ve finally decided that it isn’t necessarily such a good thing to do unless we know that the people are interested in a really serious way. It gets kind of draggy, after all, showing 1,700 people through your house when you’ve got so much work to do.”

Thanks to Gerald J. Meyer for the text and Renyold Ferguson, also of the St Louis Post-Dispatch in 1970, for the photos.

Thanks to Walter and Pat Jenkins, Tim Conley, Steve Noskowitz and Ed Pudney for helping save a place for the rest of us.