1967 – Tales From Two Lafayette Square Pharmacies

Lafayette Square is conveniently located. You can reach three different interstate highways, headed to who-knows-where, within a couple of minutes. If you want to access I-44 West, about 200 feet from the on-ramp to I-55 South, hang a turn just past the corner of 18th Street and Lafayette Avenue. It swings around this building:

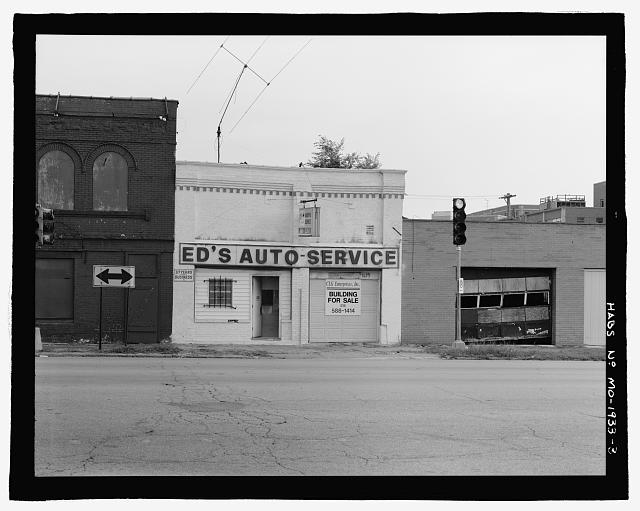

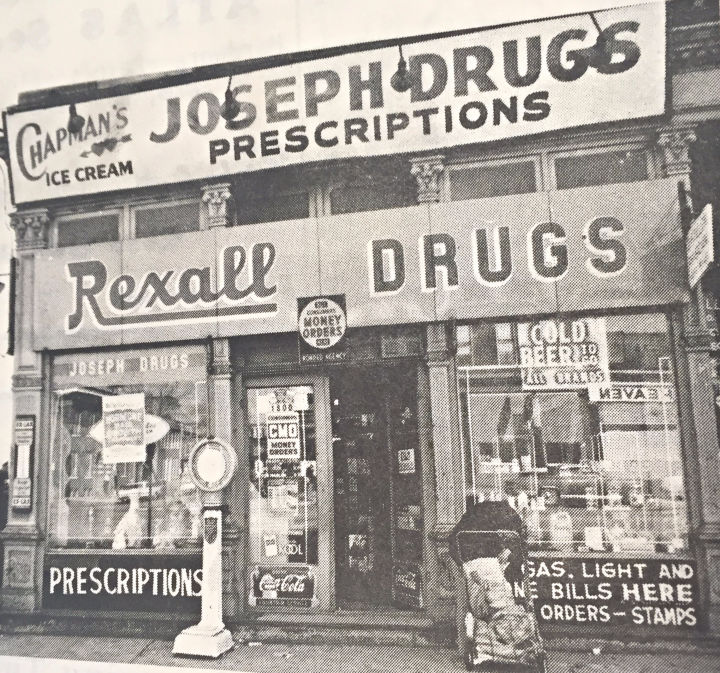

1800 Lafayette Avenue currently houses Care Solutions. It was a turn-of-the-century drug store with an original iron storefront, and a cool history. An active spot, 18th Street was a throughway then, and Ed’s Auto Service closed off Dolman from Lafayette Avenue. Ed’s met the wrecking ball in preparation for State Highway 755, aka the North South Distributor. This failed project explains why the I-44 and I-55 on-ramps lie so near each other.

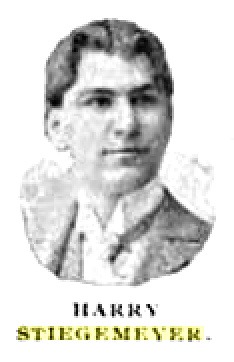

Harry Stiegemeyer and the first drug store in Lafayette Square

The first record I could find for 1800 Lafayette Avenue was a 1904 mention in The Pharmaceutical Era magazine. It noted that the Lafayette Pharmacy Company had incorporated with a capital of $5,000.00 at this address. It was owned by pharmacist Harry Stiegemeyer (1871 – 1931), and purchased from Philip Koch.

A magazine from January 1898 mentioned how young Harry, “the popular clerk at Crawley’s Pharmacy” went “up the river on a ten day’s vacation.” Crawley’s was at 2201 Carr Street, north of downtown. Owing to the distance, Harry may have lacked any existing trade when he started up his own store in Lafayette Square. Regardless, he made a go of it, and prospered in this new location. Harry managed a second venture, the Boyle Street Pharmacy at 4198 Manchester Road, from 1926 to 1930.

Stiegemeyer owned and operated his Lafayette store for 21 years, then sold the business as a going concern to Mr’s Butler and Boettner. They renamed this enterprise the B&B Pharmacy. Harry, who was a well-connected Mason, went on to a management position at Laclede Trust Company. He died in 1931, and is buried in Zion Cemetery.

The pharmacy traded hands again shortly after, as GH Boettner filed for bankruptcy the following year. It couldn’t have gone well, as he claimed debts of $24,674, and assets of $560.

A 1933 article from the Post-Dispatch related how the next manager, James A. Link, was robbed by two masked bandits. Another man entered the store just as the robbers turned to leave, and was shot and killed. For Link, it was a deja-vu of misfortune, He had been robbed at an earlier location on Morganford Road in 1927. That store went bankrupt in 1930, and Link figured he was safer in relocating to the Lafayette Avenue site.

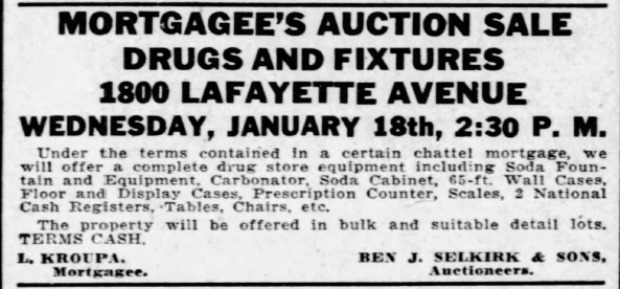

Link saw quite enough of the risk he was taking in the retail trade, and the store with all its goods went on auction though Selkirk later that year. Edward Sturgis purchased the place, again as an operating pharmacy. The interior must have been impressive with its 65 foot wall case and soda fountain.

The building’s run of bad luck continued in 1934, when a pile of rubbish apparently caught fire on the unoccupied third floor. A man and his wife, living on the second floor, escaped without assistance. Damage to the structure was estimated at $1,900, or about $28,000 in today’s dollars.

Forging ahead to 1953, the building, true to its roots, was now Kreisman’s Drug Store. It was owned and operated by Irwin Kreisman. A gang of petty thieves centered its operations in the Bohemian Hill area, just southeast of 18th Street. The Salvation Army gang, or the reform gang, got their name through persuading a judge to grant them leniency. They claimed that they saw the light and joined the Salvation Army. They even procured uniforms, as a way to win the confidence of others who they then fleeced or outright robbed. The gang hit Joseph’s drugstore as a convenient target of opportunity.

The neighborhood was indeed becoming a rough place, and Kreisman soon sold his pharmacy business to Joseph Iken.

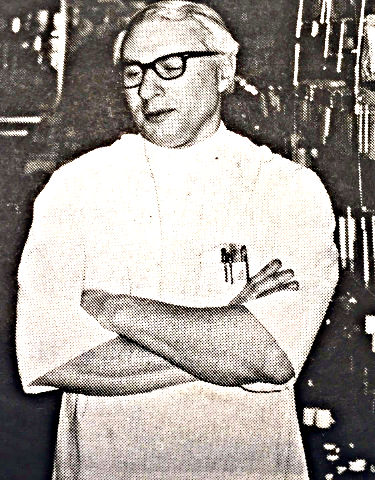

The long suffering saga of Joe Iken

In 1955, Iken suffered a holdup by a pair of robbers brandishing pistols. He opened the safe under threats to his health, then lay on the floor. The duo made off with $1,400. Armed robbers again struck the store in 1960, this time at the point of a sawed-off shotgun – and yet again in 1961.

At 9:30 a.m. on July 5, 1967, a 60-year old former convict pulled a ski mask over his face, drew a gun, and proceeded to rob the store. Joe Iken gave a signal to his clerk, who ran next door to Simon Kozloff’s shop ( Barry’s Variety Store; 1804 Lafayette Avenue) to sound an alarm. Kozloff stood on the street yelling for help, and the crook, alert to the commotion, fled out a back door. Kozloff and Billy Moore, a 16-year old local boy, gave chase north on 18th Street to an alley. The man turned and fired wildly at his pursuers. Two other men came from a tavern and helped corner the robber in the alley, where he shot and killed himself.

Joseph Iken, a decorated veteran of World War II and president of the Missouri Jewish War Veterans, continued to stick it out at the pharmacy, despite the odds.

Another druggist reflects on the times

The only other drug store in Lafayette Square in 1967 was the Park Avenue Pharmacy at 1937 Park Avenue (Now Frontenac Cleaners). It was then in the process of closing shop. Herbert Breuckmann, a well-liked local pharmacist, owned this enterprise. The Post-Dispatch headlined its demise as “The End Of An Era”. Olivia Skinner wrote at length about the former elegance and subsequent decline of the neighborhood. In the 20 years preceding closure of the store, the area around the park diminished by more than a quarter of its residents.

US Census Bureau stats showed that by 1960, the four tracts surrounding Lafayette Park lost 13,669 of its 1950 figure of 35,327. Many of its former mansions, repurposed as boarding houses, had become empty shells.

At the time of its closure, the building at Park and Mississippi Avenues accommodated a physician who practiced for 35 years on the second floor, and an insurance agent on the third. All three men grew up in the neighborhood, and held an unofficial wake for their businesses, as the reporter listened in. Herbert Brueckmann worked at Park Avenue Pharmacy since he was nine years old. He started out working two days a week and made 25 cents and a scoop of ice cream per day. Brueckmann added that he was happy to do it, as “there was always someone waiting outside to take your job.”

“Last year a man from the government offered me a $5,000 loan to fix up the place – new paint, new linoleum, all kinds of things. I told him it wouldn’t do any good at all unless he could put more people on the streets.”

The physician interjected that he’d seen ten drug stores close in a 20 year span, and “if Herb can’t make it, nobody can.” Herbert reminisced that the store used to deliver until 11 p.m.

“People would drop by after supper for soda and to buy things. We had a bustling soda fountain business too. We made our own ice cream; before air conditioning. In the summer of 1945, we sold 2,700 gallons.”

The insurance man recalled that hurt kids used to stop at the pharmacy instead of going home. Herbert would wash a wound, bandage it, and give the child a piece of candy.

“He gave change and made phone calls for people who couldn’t read the directory. For people who couldn’t write, he’d address birthday cards, and even write letters. People would hand him a nickel, a card or piece of paper and a pen and say, ‘You write it’. And he did.”

All three agreed that the real change came with World War II. People from ‘the country’ took defense jobs, and then sent for all their relatives. They noted that civil rights legislation opened neighborhoods to the demographic changes that caused residents to relocate to “Arnold and Lemay.”

In a trend that would repeat through the rest of the century, they also blamed the automobile for making it possible to head out to a newer and larger supermarket that sold “groceries and drugs and toilet paper – whatever you needed. I have to buy a dozen cans of hair spray at $1.50 apiece, but the supermarket price is $0.89. Then the ice cream trucks drive by and take that business too.”

Herbert never missed a day’s work, although he gave all credit to the assistance of his wife. “Without her help I wouldn’t have been able to do what I did. There were times I should have stayed at home.” Raising five children, the two always felt they needed the income.

Choosing like others chose; and a neighborhood in decline

The writer contrasted these wistful memories with Herbert’s recollection of a drive he took to canvass the area, and how the homes he saw were hollowing out from the river to Jefferson Avenue and from Chouteau to Geyer. The empty houses convinced him there was no point in remaining. Her description of Lafayette Park in 1967 was forlorn:

“the sunny green park surrounded by solid mansard mansions reminds the visitor of a bravely smiling dowager fallen on evil days and badly in need of dental work. Many houses are vacant, with broken windows and boarded doors. Others have been pulled down. Passersby risk turned ankles on missing section of brick sidewalks. Back yards are piled high with broken washing machines, rusty bed springs, rags and old automobiles. Lines of laundry flap in the wind.”

Herbert Breuckmann added, “Twenty people at a time used to get off the streetcar at the corner here, and many would come into the store. Now most people are off the streets by dark – they’re afraid to be out, and I wouldn’t dare send a delivery boy.”

The insurance agent said. “Herb would help you out. I used to come in here and get a soda, shoot the breeze with Herb, and pick up money that my clients would leave for me.”

As the character of the neighborhood changed, Herbert became more careful of the business he accepted. Realizing that some of his customers were chemically addicted, he grew cautious about sales of paregoric and airplane glue. He got more calls about accidental poisonings, and gave instructions on how to induce vomiting. Often, he advised a caller to get the person straight to City Hospital.

And with the decline, there were more fights on the corner. Shoplifting became a problem, and youngsters tried to jimmy the telephone coin box outside the store.

The doctor from upstairs said, “the police used to play checkers with the old men in the park. Now they’re never still. They have their hands full with juvenile delinquents and winos.” There were three break in attempts in 1965, and the store still bore scars at the transom in the back, the ceiling, and the front door. Breuckmann did, however, consider himself lucky that he had never been forcibly robbed.

His wife then showed up beaming, and rejoiced that her husband was going to take a new role as pharmacist for St. Luke’s Hospital. “He’s worked 75 or 80 hours a week here,” she said. “Now Herb can come home and be a husband and father to us, just us, and not to this whole neighborhood.”

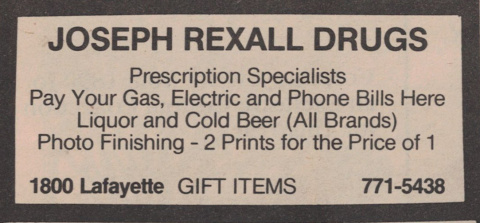

The last pharmacist standing

This left Joe Iken at 1800 Lafayette Avenue waging the last stand of the neighborhood pharmacy in Lafayette Square. He allied himself with Rexall, and was still very much in business when the above ad appeared in the Lafayette Square Marquis in 1983. Joe advertised that he collected gas, light and phone bills, saving folks the cost of postage. He witnessed a certain amount of rebirth in the neighborhood, and held out for a long time. In an appropriate move for a community that soon trended toward the gentry, the distinctive building at 1800 Lafayette had, by 1997, become the Bark Avenue Grooming Shop, and first home of St Louis City’s Stray Rescue.

Echoes of the past still persist around the Square – the telltale ghost sign above reflects a time when drug stores were the commercial hubs of a neighborhood. When you make the turn onto the I-44 ramp, take a quick look up and give a nod to Harry Stiegemeyer, who may have been the dean of Lafayette Square pharmacists. Todays corner drug stores have given way to chain box concepts like CVS and Walgreens. They carry a soup-to-nuts range of products, but try to get someone there to write a card for you!

Thanks to research sources including:

Various St Louis Post Dispatch and St Louis Star And Times stories; especially “Lafayette Square At End Of Era” by Olivia Skinner in the July 9th 1967 Post Dispatch. How appropriate, as 1969 marked the birth of the next era with the formation of the Lafayette Square Restoration Committee, now in its 50th year.

The Pharmaceutical Era Volume 31 p 97; D.O. Haynes and Co. New York; 1904

Various Goulds directories, courtesy of Mercantile Library

The National Register via DNR.MO.GOV

National Association of Retail Druggists (NARD) Journal Volume 37: 1923