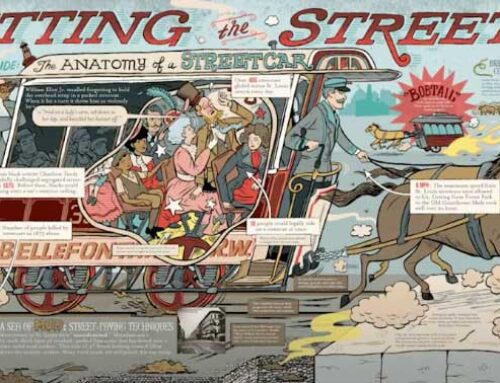

The New York Times of May 27, 2021 has a fascinating study into the long term social and economic costs of America’s drive to accommodate the automobile after World War II. It wasn’t just St. Louis whose ethnic enclaves were carved up by eminent domain and big money. The Times points out that hundreds of neighborhoods nationwide similarly lost out to the same process.

A question worth considering is how Lafayette Square managed to avoid becoming sectioned off for the North-South Connector, I-55, and I-44. Parts of our community were lost, but most of it survived intact. This wasn’t by dumb luck.

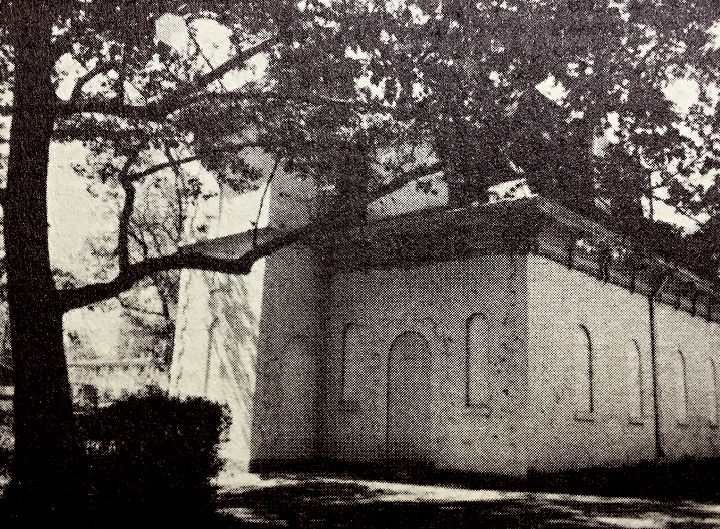

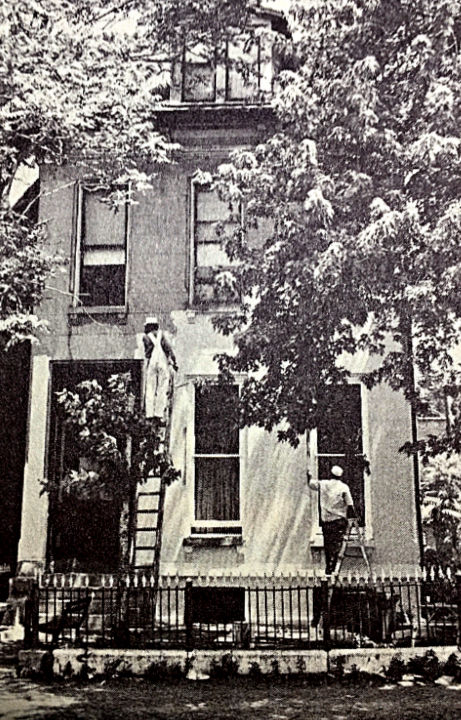

Lafayette Square as it stood in 1971

Fifty years ago, in the autumn of 1971, the St. Louis Plan Commission, in conjunction with the Lafayette Park Neighborhood Association and Lafayette Square Restoration Committee, published a Lafayette Square Restoration Plan.

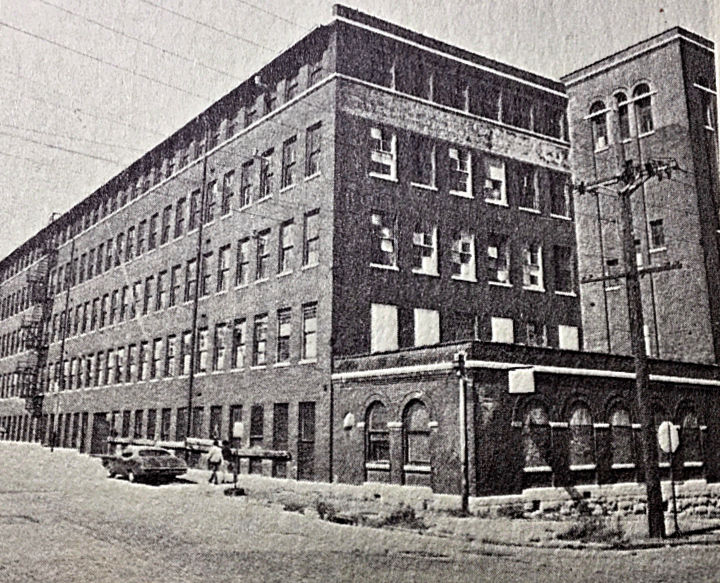

At the end of 1970, there were 88 single family residences, 67 boarding houses, and 331 multiple family units in the Square. Nearly a quarter of all living spaces took the form of rooming houses. This, for a population of 3,255 people.

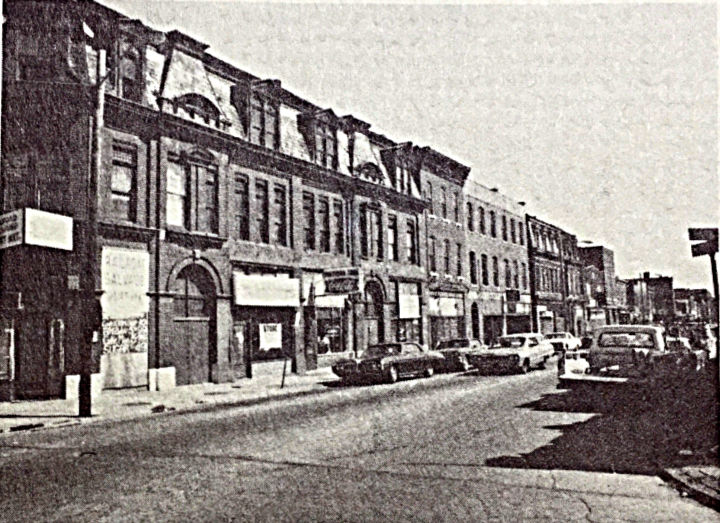

As interesting as what was occupied was what was not. There were 59 vacant properties, and 29,000 square feet of empty commercial space. The 1970 census showed that of 1053 residential spaces, 389, or nearly 40%, were vacant.

By contrast, the census of 1960 reported 5,000 residents and 1760 residential spaces. In ten years, both neighborhood population and housing in Lafayette Square managed to shrink by 40%.

A survey taken in spring of 1971 revealed that of 429 structures, 41% required major rehabilitation and nearly 18% were debatable as to whether restoration was feasible. Only 5%, or 22 structures in Lafayette Square were deemed sound. Wholesale demolition loomed in the near future.

The future hinges on a highway through the ‘hood

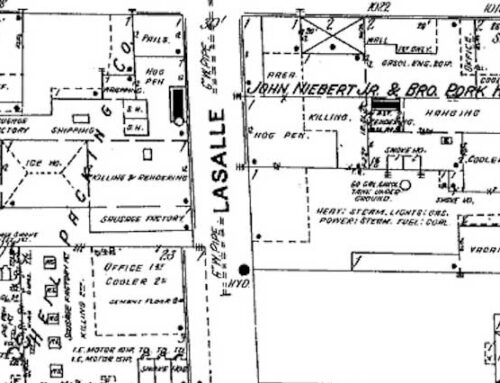

The pall hanging over every neighborhood development idea at that time was the planned North-South Distributor. This highway was considered inevitable in 1970, and would require “displacement of historical structures.” Relocating buildings from the highway’s path was problematic. The plan noted “without a substantial increase in home values, few structures will be moved.” Physically, many of these buildings were structurally sound, with weathered but worthy brick and mortar. The exterior woodwork in these homes was considered a wreck.

Most Lafayette Square homes were built before indoor plumbing was the norm, and lacked modern electrical circuits and central heat. It was common then to use existing gas pipes as conduit for running electrical lines. Others used surface mounted wiring. Coal furnaces and gas space heaters were both inadequate and unacceptable.

The Lafayette Square Restoration Plan was intended to develop vacant properties while replacing dilapidated and incompatible properties. A goal was to increase residential density back to 1,600 living spaces, primarily one and two family units. The resulting 5,000 residents could then support community facilities and services, creating a virtuous cycle of recovery.

Something to build on

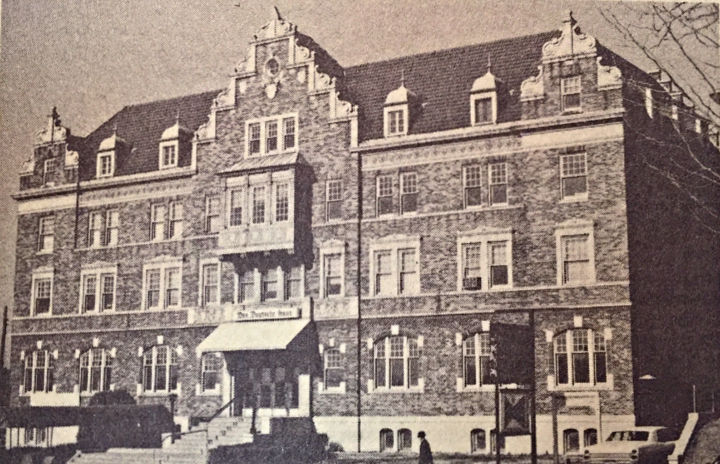

A quick overview of neighborhood assets listed the Caroline Mission as a nursery school and recreation area for small children, The German House with its bowling alleys, the Gateway Temple Church with a nursery and school through third grade, and a pool hall.

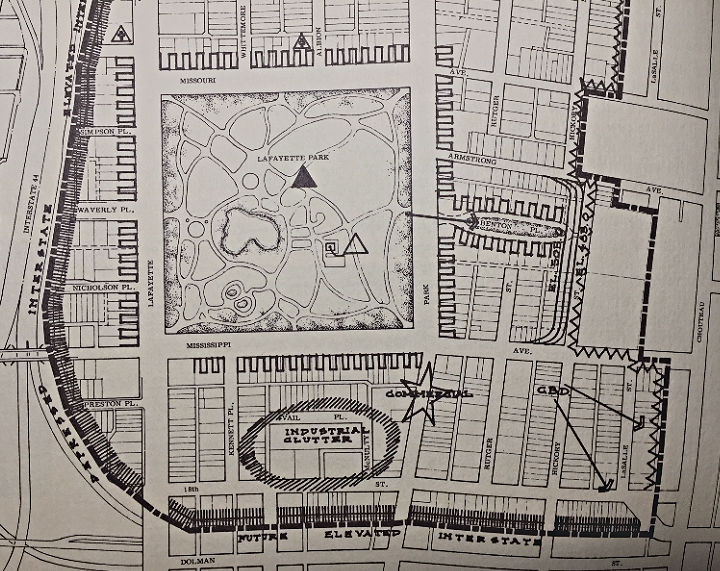

New residential development was proposed for the Northwest quadrant and between Vail Place and 18th Street, in accordance with the city’s historical district ordinance. New multi-family dwellings were imagined for the area between Lafayette Avenue and I-44. In addition, 360 structures stood to be restored under the plan. In 1971, there was a citywide ban on construction of attached row houses. A recommendation was made to allow this style, formerly common in the Victorian period, to be built in Lafayette Square.

Even back in 1971, the double-edged nature of gentrification was recognized, although measures to address it were left vague. “Opportunities should be available for existing residents if they wish to remain in the neighborhood,” didn’t read like much protection for the folks the area was being improved for. A relocation strategy, through the city’s centralized relocation agency was mentioned. Given its history of dense high-rise development in poor areas, this seemed more a bug than a feature of the plan.

The Strip and the Park

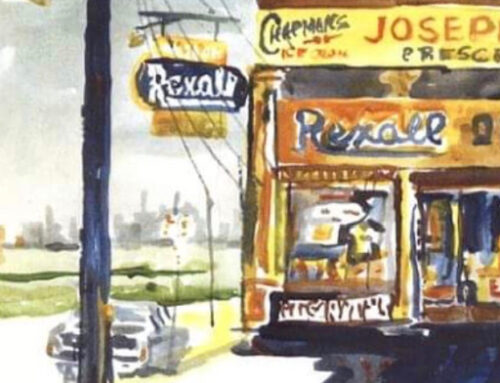

Commercial development was to center on the area at Jefferson and Lafayette Avenues. The commission hoped that the German House at 2345 Lafayette Avenue would play a key role in tying the neighborhood to this commercial area. It stated, “the German House should expand its present role and become more of a social and cultural center for the city as a whole. It deserves the support of all St. Louis citizens, particularly those of Geman ancestry.” The plan also recognized the value of the Park Avenue strip from Mississippi Avenue to 18th Street as a vital commercial zone.

Lafayette Park still accounts for nearly 30% of the neighborhood space. In 1971, the lower lagoon in the grotto lay empty. The plan ambitiously called for replacing the ruined bandstand, restoring the boarded-up park house for use as a museum and visitor center, and recommended a more long term goal of complete fence reconstruction.

The report asserted that every street in the area was in need of repair or resurfacing. As left hand turns from Jefferson to Park and Lafayette were prohibited, cars and trucks used Albion and Whittemore Places as thoroughfares.

Recommendations included closing access to Whittemore and Albion from Jefferson Avenue, extensively landscaping the neighborhood and park perimeters with new trees, closing industrial vehicle access from Chouteau Avenue, widening Park Avenue along the business district and adding an elementary school on Missouri Avenue between Rutger and Hickory Streets.

The plan led to results

The plan did lead to much of this, in addition to elevating I-44 20 feet above street level at Jefferson and depressing it to 20 feet below street level at Mississippi Avenue. This served to improve the sight lines and muffle sound from the highway. The community also followed the recommendation to create a unified neighborhood voice, and vehicle (the LSRC) for producing brochures, news releases and lists of available properties.

Thought was given to forming a restoration corporation, working in conjunction with a major developer. This would prevent real estate speculation while the area redeveloped. Having the neighborhood as an active partner in the corporation would prevent a developer from proceeding heedless of the neighborhood’s wishes.

The plan called for designating a Historic Development District to ensure its survival. This would be followed by the neighborhood working with the City Plan Commission to develop historical and architectural standards for restoration and preservation. As it played out, The ordinance creating St. Louis’ first historic district passed the following year, and Lafayette Square was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. The neighborhood also received a $25,000 loan from the National Trust to purchase endangered properties – a loan that was fully paid back.

Local thought leader McCue Approves

McCue summarized by pleading that such “neighborhood effort, for heaven’s sake, is something that St. Louis cannot buy and has a hard time even persuading to come into being. Here it is already, and it needs to be encouraged.”

And in the fifty years since…

The half century that followed the city’s first redevelopment plan for Lafayette Square saw consolidation of the Lafayette Park Neighborhood Association with the LSRC, which became the official neighborhood citizen’s organization. Under a committed group whose leadership changed (and still does) yearly, it’s amazing what has been achieved. First time visitors to Lafayette Square marvel at the Victorian era and Gilded Age architecture, the lovely park, and top-tier restaurants. How was it all saved, when everything around it changed with the times, and not often for the better?

It’s a fifty year long story one should be here to fully appreciate. This is a special place, but wasn’t preserved in amber, or uncovered like King Tut’s tomb. It was the product of residents taking a long shot on an old horse. Or an old house, anyway. The originals who drifted here in the late 1960s may not have fully recognized the distinction between vision and hallucination. We’re all richer today for their persistence in creating a diamond from a lump of coal. Their path was paved with obstacles; avoidant realtors, balky bankers and insurance companies, lack of basic services and infrastructure. They prevailed, saving a building, welcoming new residents, co-oping their needs, one step at a time.

Thanks to research sources including:

Lafayette Square Restoration Plan from the St Louis City Plan Commission; Fall, 1971, in cooperation with the LSRC and LPNA

George McCue of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch; Sunday, December 19,1971; Page 51

The New York Times article cited at the beginning of the essays is here: NYT Article. Highly recommended.